Trump Tax Plan

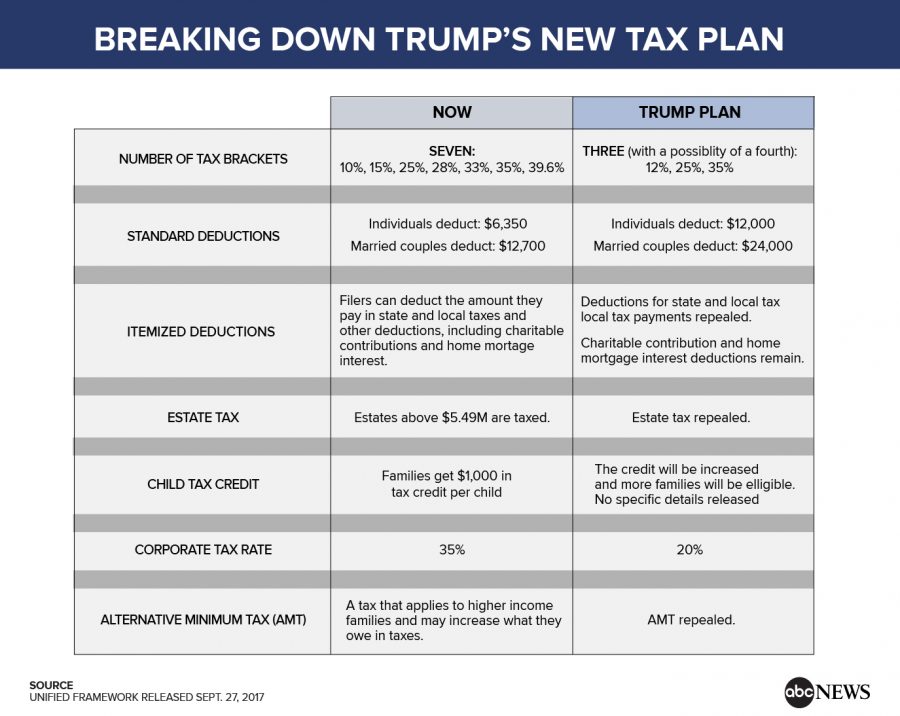

Trump’s new tax plan is nothing short of taking from the poor and giving to the rich. Right off the bat the wealthy get a tax reduction. They only have to pay 35% on their pay charges (a decrease from their previous 39.6 percent). Right now, this rate applies to basically any salary above about $418,000. Trump says he would approve of Congress raising assessments on the rich, but he isn’t requiring they do that. The greater tax reduction for the rich is the end of the domain assess, or the expense families pay when an advantage like a house or farm worth over $5.49 million is passed down to a beneficiary after somebody bites the dust. Trump’s arrangement scraps this domain assessment altogether. But the real question at hand is what happens to the middle class.

There’s a lot of details left for Congress to fill out. Under the plan, America will have just three tax rates: 35, 25 and 12 percent, but we don’t know which rate someone earning $50,000 or $80,000 will pay. What we do know is the standard deduction (currently $6,350 for individuals and $12,700 for married couples) will essentially double. This means that a married couple earning $24,000 or less or an individual earning $12,000 or less won’t pay any taxes. But the plan also eliminates what’s known as the additional standard deduction and the popular personal exemption. Some filers may end up worse off after these changes.

Trump’s plan also promises a “significant increase” to the child tax credit (it’s currently $1,000 per child) and that middle class Americans can keep using the mortgage interest deduction as well as tax breaks for retirement savings (e.g. 401ks) and higher education. But it eliminates the state and local tax deduction, which is used by many in high-tax states like New York and California.

Another question people should be asking is what happens to lower income citizens.

A senior White House official told columnists Tuesday, “We are committed to making the tax code at least as progressive as the current tax code.” Translation: The poor shouldn’t wind up paying more than they do now.

In principle, expanding the standard derivation should imply that more Americans pay $0 in charges, but it depends a great deal on duty arrangements and whether Congress cuts wellbeing net projects that assist the poor to pay for tax reductions. Top Republican authorities have not chosen what to do with the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which is broadly utilized by the working poor to enable them to lessen their duty charge and recover a little measure of cash from the legislature.