Since the summer of 2023, we’ve all seen at least a few videos playing off of certain microtrends that centralize around the “girl” experience. Whether it be “girl dinner,” “hot girl walks,” or “girl math,” the idea of “girlhood” has become more than just a phase in a woman’s life but a way of bonding through screens and across the vastness of the internet. At the same time, it has also become a source of criticism, with some arguing that the trends promote a neo-traditional view of girls and women, reviving harmful stereotypes that women, for centuries, have attempted to separate themselves from.

Like most teenagers, I spend more time than I’d like to admit online, scrolling through the endless void of “POV” (point of view) videos and aesthetic outfit inspo (inspirations). A few weeks ago I was stopped mid “doom scroll,” by a video (which I have since struggled to locate), in which two girls were playing pool- albeit poorly, as was the focus of the video. The video was accompanied by a caption along the lines of “girlhood.” There was nothing particularly shocking about the video, and it certainly wasn’t unique. I had seen hundreds of videos poking playful fun at certain experiences deemed “girl-coded,” but this one felt different. I think it was the first time I had recognized that the punchline of these lighthearted moments seemed to be overt misogyny.

I scrolled through the comments, and a few had begun to point out the same thing. In this video, the thing identified as “girlhood” was two girls being bad at sports. It immediately reminded me of another trend, a sound from TikTok, with a female voice exclaiming, “You are literally a girl, why are you hating like a man?” This question made me curious and, suddenly, I began to examine all the “girl-coded” media under a much harsher lens. Were the videos about “girl math”, “girl dinner”, and “girl problems” as jovial and innocent as I had been perceiving them? Or were they signs of much deeper-rooted issues: internalized misogyny and a perpetuation of societal patriarchy?

Most of the videos and posts about girl math, for example, dealt with the impulsive and irresponsible financial decisions women made and their excuses for certain such purchases. One post from @altardstate on Instagram wrote, “Girl Math: If you pay for something with cash, it’s ~free~.” Another, from @larissaemily, said, “Girl math is avoiding shipping costs by buying more.” The problem many people find with these posts is that they perpetuate the stereotype of women as financially illiterate. So, when looking through the harsh lens I’ve acquired, it seems a bit weird when these types of statements are being used as marketing techniques for businesses that cater predominantly to women. People like lash and nail techs are marketing their services with girl math. “Girl math-lash edition: paying for my lashes in cash so they are basically free,” posts @chloluxe, a lash and brow artist. Then again, these businesses rely on female customer’s support and establish themselves in their industry by bonding and sharing parts of the “girl” experience. As Kelly-Ann Winget, the founder of a solo-female-founded private equity fund, explains, budgeting advice usually includes cutting out things that make people (typically women) happy. Things like manicures, trips to the hair salon, the occasional shopping trip, or even money spent on hobbies are first to get cut from budget lists. So when female-centric businesses advertise with these “girl” trends, it’s more like they’re saying “solidarity sister” than implying women are financially irresponsible.

Although these hobbies are not strictly synonymous with girlhood, it can be frustrating when being financially responsible means sacrificing a bit of happiness. Like everyone, women deserve to allot some time and money on things that make them happy. Girl math is a way for women to justify spending money on themselves because they feel that others would judge them for how they spend money, deeming it unconstructive and materialist. Girl math is not automatically a signal of financial illiteracy or a cry for help to mansplaining men because most adult women do make responsible financial decisions for themselves and their families.

Like Winget says, “Girl math challenges conventional financial rationality, providing a perspective on spending’s value instead of discouraging purchases…we see this with women that have income, not anyone experiencing financial difficulties,” she continues by saying, “If women are using girl math to justify spending that doesn’t derail their financial well-being, that is a good thing. In the end, it shows financial responsibility and actually pausing-+ to think about the impact of a purchase before it’s made.” Purchases should be made by weighing the value of a good or service- and although responsibility should come first, splurging occasionally for something that will make you happy is valuable in itself, so what if girls want to bond over their hobbies?

In a world where women are often pitted against each other as a result of beauty standards and society-perpetuated insecurities, it’s important to have a corner of the internet where girls can be content in the fact that they are not alone- even if it’s a “girl math” experience as minor as “washing your hair so it lines up your plans.”

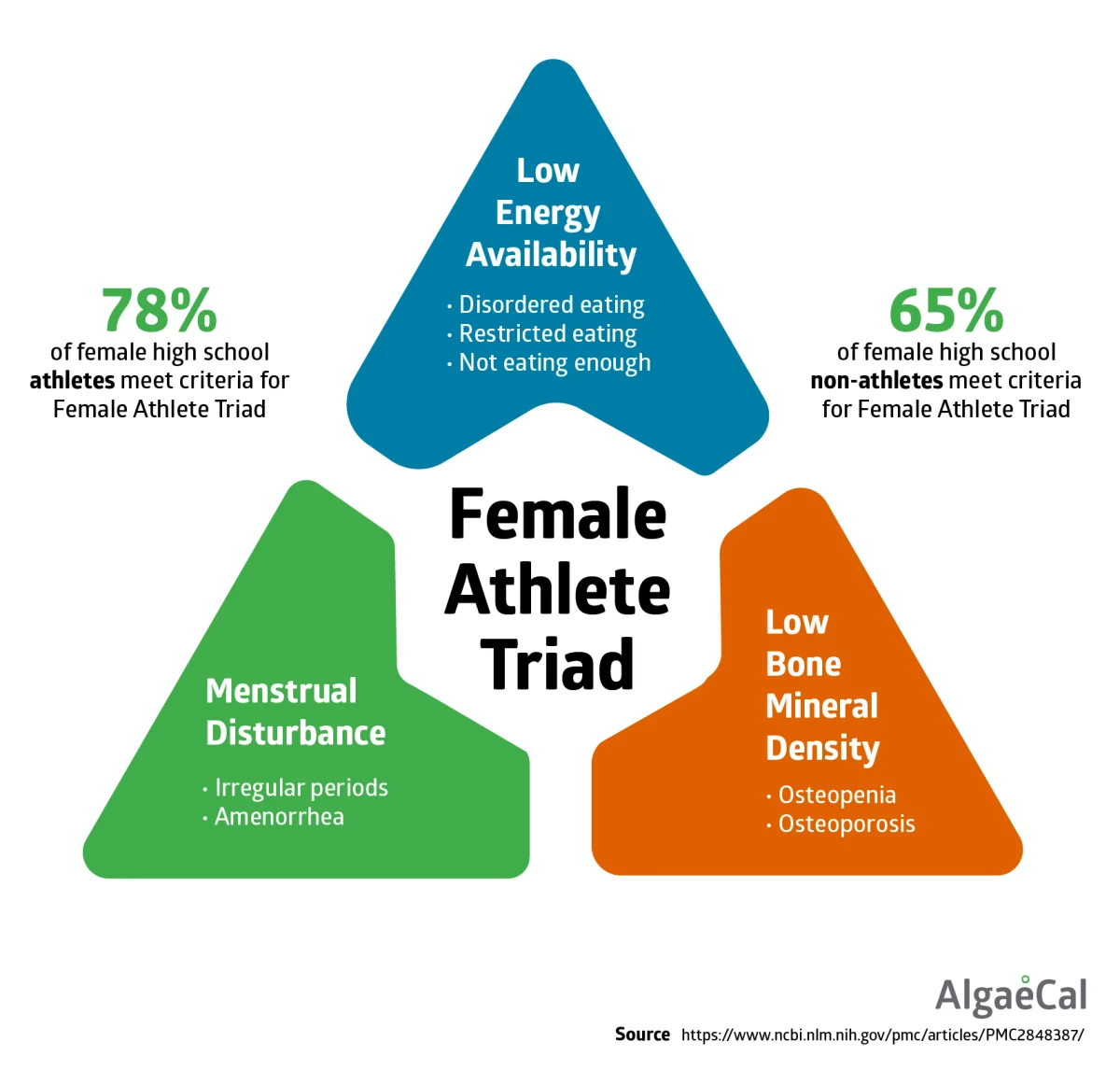

Another “girl-coded” social media trend follows the idea of “girl dinner,” where “girls” compile a makeshift meal resembling a charcuterie board of leftovers or small bites. The original creator of the “Girl Dinner” TikTok sound spoke about her original intentions, explaining that her video was like sharing a lighthearted secret with other women online, curious if other women related. The video soon went viral and became a trend of other women sharing their “girl dinners”. The trend almost immediately received a backlash from concerned viewers, worrying that the videos promoted disordered eating and linked a lack of a balanced and nutritious diet to girlhood itself.

While these specific videos are certainly not a root cause of eating disorders in women (we have decades of Hollywood beauty standards and capitalist agendas to thank for that), the way that these videos could be perceived is what makes them tricky. With the already toxic image of what the perfect body and lifestyle look like, which the modern woman sees through photo-shopped influencers and carefully curated “what I eat in a day” videos, in some cases, “girl dinner” videos could act as a supplement that builds off of people’s already damaged perceptions of what they eat. Seeing the haphazard “meals” called “girl dinners,” viewers mistakenly see the meager portions as an everyday thing. The creator of the TikTok trend affirms girl dinner isn’t a daily thing, reminding people that“girl dinner can look like anything that you need, and we don’t necessarily know what someone has already eaten that day.”

Separated from these perceptions, the videos could have existed as the relatable content they were intended to be, but in a contemporary America where “0.3-0.4% of young women…will suffer from anorexia,” that may be impossible.

Under these perceptions of “girl dinner” videos, it is also important to point out that by drawing a line between eating disorders (which these videos are being perceived to glorify) to being a girl, you are excluding other individuals who may be suffering eating disorders as well. While 0.3-0.4% of young women suffer from anorexia, about 0.1% of young men also do.

Regardless, there is an underlying tone of misogyny in all of these videos, from the girl math to girlhood videos where girls post about their “girl problems” under videos where they have to choose between two outfits or other situations that could be deemed superficial. So where does this come from? Why are women willingly finding solace in trends that are laced with stereotypes?

“Girlhood” trends can act as a way of bonding over the internet but may also act as a facade to momentarily hide from the “real” problems women face on a daily basis. By sharing the more trivial dilemmas we face, like deciding when to wash our hair or what shoes we should wear, we allow ourselves to take a step back from the grueling reality of sexism and microaggressions in the workforce, athletics, and relationships.

I think many people have sort of become blind to the fact that sexism is still thriving, especially in the community we live in, because there are so many signs that both physically and metaphorically blast progressiveness and support. Still, slight but harmful misogyny continues to haunt me, from condescending remarks from my rec soccer coach to comments from elementary school teachers connecting my quiet demeanor to politeness and a ladylike quality, not to mention disrespect from male classmates. These videos offer momentary refuge and solidarity in the simple fact of being a girl.

But why is it girlhood that we find solace in rather than womanhood? By definition, the two terms are pretty different. Girlhood refers to adolescence and often includes coming-of-age experiences, while womanhood is the state of being an adult- a woman. In recent years there has been a shift in how Americans view marriage, and people are waiting longer to get married and have children or choosing not to marry at all. The marriage rates have gone down, and the age at which most matrimonies occur is going up. This may not necessarily have much magnitude to this issue on the surface, but when we remember that our society has long existed as a patriarchy, it may pose some significance. For centuries, the value of a woman was placed on her ability to have children and care for a husband. Now that traditional gender roles are becoming less popular, I find it possible that women are still not separating their womanhood from patriarchal standards and instead, feel it a more fitting representation of themselves to empathize with girlhood which is something that has historically been less attached to reproduction and marriage.

In conversations about what defines a woman, many arguments lead back to the idea that “a woman” is defined as a person who menstruates and can have children. This is often refuted by the argument that cisgender women may also not have these capabilities but are still considered women. This debate displays a prolonged attachment to old concepts suggesting that women may be subconsciously identifying with “girlhood” rather than “womanhood” because of this. Women are embracing being a “girl” because being a “woman” still implies the need to be a mother or a wife, hinting at bits of lingering internalized misogyny or at least harmful perceptions of what being a woman means.

Despite these misogynistic leftovers, these videos also display an overwhelming sense of joy in identifying with girlhood and femininity, something that younger adult women who are mostly participating in the trends lack as teens are children. The word girl has also begun to be used as an adjective to describe blissful little moments in life, and the recent “girl” trends celebrate femininity across the board, a welcome shift in comparison to harsh reality.

Like most things, the internet blew the relatable anecdotes of girl math and girl dinner out of proportion, creating grounds for social commentary about the stereotypes still oppressing women. Although I usually find myself annoyed at the constant debates held in social media comment sections, I found this one fascinating. Perhaps it was because I saw value in the fact that both men and women were questioning the meaning of certain rhetoric. It’s important to recognize toxicity and stereotypes when we see them, but there’s also value in allowing girls and women to exist on the internet as a community where relatability and common girlhood experiences connect us. While some find the obsession with girlhood belittling, reducing women into childish figures, the carefreeness of girlhood is what tethers people: the innocent desire to just be happy.