Substance abuse among teens isn’t a new story. The same age-old formula of teen angst mixed with peer pressure has left centuries’ worth of teenagers hooked on drugs and alcohol well before they walk the stage with their diplomas. Past generations grew up surrounded by tobacco, smoking on planes, in restaurants, and, yes, school bathrooms. While smoking is less common for Gen-Zers, substance abuse remains prevalent. Vaping has taken over many teens’ lives, what’s different with this generation, however, is the rhetoric surrounding smoking has painted vaping as a safer alternative. However, it’s absolutely not. Even with an expansive sea of information on the internet regarding the dangers of vaping, marketing campaigns from popular vaping companies have led today’s teens into a blind addiction that is casting an ominous haze on their future and the school bathrooms.

When you walk into the typical bathroom at West Orange High School, you are met with a stuffy cloud that smells of fruity chemicals. It is the residue of a vape session held during the passing periods between classes, before or after school, or even during class itself. If you are lucky, you may even receive a fresh exhale of vape puffed into your face as you maneuver through a crowd of your congregated peers as you attempt to find an unoccupied stall.

“Typically, when I walk in, there are anywhere between one to six students vaping,” says a junior at WOHS, who has experienced the slew of vapers in the bathrooms during the day to get their “fix” of nicotine. Informal polling shows that, on average, students agreed that at a time, one could see around 1-7 students vaping in the bathrooms. “They usually go in groups,” the student explains. In recent weeks, a group of students were also caught not only vaping but also drinking in one of the girls’ bathrooms in the middle of the academic day.

Administrators at WOHS are generally aware of the gravity of what Mr. Del Guercio, the dean and Disciplinary Officer for students with last names starting with A through DER, calls an “epidemic.” Even so, the easily concealable nature of vaping allows students to be relatively discreet, especially since school bathrooms are the primary hideouts for vapers. While the security cameras are always rolling in the hallways and lunchrooms, the bathrooms can’t have cameras, forcing administrators to come up with more creative ways to catch and prevent their students from vaping.

In recent weeks, the WOHS administration locked most student bathrooms so that they could not be opened, even by students and some staff IDs. The decision was intended to dissuade students from vaping and make it easier to track down perpetrators. A few bathrooms have also been closed “because of maintenance,” and a few others have broken card readers that fail to unlock the door upon scanning a student ID.

This “intervention,” as Del Guercio called it, sparked outrage amongst students who complained about the inconvenience. Female students worried about being able to find an unlocked bathroom while on their period, and others protested that locking more bathrooms only made students miss additional instruction time. The lack of open bathrooms soon caused a backlog of students, on one occasion, a line of about 10 people waited for a stall in a three-toilet-girl’s restroom as few other bathrooms were unlocked.

On February 15, another WOHS student posted on Facebook to West Orange 411 asking, “Is there any reason WOHS is locking all the bathrooms? For more than two weeks, they’ve locked the bathrooms and only kept one open on each floor, making me (a disabled student), and others have to walk around every floor to try to find the one open…but now they just locked all of them today. This is weird, right?! They try to say it’s because people are setting off fire alarms in the bathroom, but people still need to go to the bathroom. Am I the crazy one here?” Commenters agreed, replying that “this is an accessibility issue” and that the situation has “[violated] [our] right to reasonable accommodations.”

Although all bathrooms, besides ones closed for maintenance, have since been unlocked as a result of the undue “stress on the custodian[s],” says Del Guercio, the initial vaping intervention method put in place as a “solution” shocked students, especially those who find the real problem to be WOHS staff turning a blind eye to the crisis at hand.

On February 23, a WOHS student shared their experiences, “One time I went to the bathroom and some girls were vaping, and it was in the morning and…[a] security guard, comes in and lets them go and they all put their heads down and scurried out,” the student passionately retold the story, their anger swelling, “I’m just confused about why they say vaping such a big problem but [the security guard] just watched them all vape and said your lucky I’m not reporting you guys.” The student’s anger was directed toward the security guard, acknowledging that it was their understanding that reporting vapers fell under the numerous responsibilities for student safety and security.

Other students described their experiences in class where teachers knew one of their students was high in class but failed to report them. “Freshman year, I remember this kid was in a class, and he accidentally dropped a vape on the floor, and the teacher was like, ‘I didn’t see anything,’ and [she said] ‘Just put it back in your bag,’ ” a student shared, “That’s why it’s a problem…because they’re not trying…because they don’t care enough to report them.”

“They’re talking about how important it is, and they don’t even care about the well-being of these people.” another student said, responding to their friend’s story. The same sentiment was noticeable in each account- a feeling of insignificance and neglect.

After the locked bathroom intervention failed, the school added a new “duty” for teachers teaching at least five classes: Bathroom Duty. Every teacher with 5 classes usually has two free periods (for preps and lunch), the third free period, out of the rotating drop schedule of 8 periods, is a duty period where students may be located in the hallways or lunchrooms to ensure students’ cooperation and safety. Those assigned to the newly added “Restroom Duty” are responsible for recording students who enter and exit each bathroom by noting their name and whether or not they have a “Smart Pass.”

With the bathrooms unlocked and some accessibility renewed, things seem to be better for the non-vaping student population. However, with less visible attempts at vaping prevention and the apparent disregard for student well-being by select staff members, students are worried. Is the crisis being handled at all?

Due to the failure to report vapers by some teachers and security guards and the simple fact that students are turning bathrooms into concealed hotboxes, it’s hard to catch offenders. But that doesn’t mean the consequences aren’t substantial. Pages 24 through 28 of the WOHS Student Handbook outline an extensive series of consequences for students found vaping or using other drugs, including suspension and a “medical examination” followed by mandated “medical clearance” before returning to school. “If the testing results in a positive result for illegal substances, further discipline may be applied,” the handbook specifies. The length of suspension is determined by each offense and is extended for each habitual offense.

Del Guercio explains that an additional step is in the process of being added to this list: a day of restorative practice. Students caught vaping will have to complete the ASPIRE (A Smoking Prevention Interactive Experience) program, an anti-smoking and vaping education training course. The program is a “ three or four-part module” run through a restorative practice center and consists of videos, questions, and lessons. The program ends with a mandatory quiz that the student must pass to complete the course. The goal is to educate students and “have them reflect on basically the dangers of vaping,” says Del Guercio, who describes the course as a “kind of supportive measure” rather than a punishment. According to Del Guercio, this program is an additional measure “that the school is going to be putting [in] effect as early as I think today [February 20].” He explains that the school had been working on creating ASPIRE accounts, which they had been approved for, that very day.

The results of the student’s day spent in the restorative practice center would be reviewed by parents, and the WOHS student assistance counselors (SACs), who are part of a subsection of the counseling department focussed on meeting students’ mental and emotional needs. According to the district website, they are responsible for “assisting families and students with alcohol and drug issues by connecting students and families to community resources.” Such resources can be found here.

In addition to speaking directly with students, in the past, the SACs have held “one or two programs per year,” says Del Guercio, which work to directly reach out to and educate concerned parents rather than teens. This year, he believes that a DEA (Drug Enforcement Administration) agent has been invited to speak as part of “Hidden in Plain Site, a program for parents to learn how to identify if their child is hiding drugs, including vapes, within their homes.

“We have you here until like 3:30, sometimes later, but obviously, you’re at home all the rest of the time. So I think it has to be a team effort with parents,” says DelGurcio, stressing the importance of parent education.

Of course, despite the resources the SAC counselors offer, most addicted teens may not feel comfortable reaching out for help with substance abuse or even have the ability to diagnose their situation as an addiction in the first place. Del Guercio estimates that discipline officers “maybe [catch] one [vaper] every couple of weeks.”

“You can have like three [in] one week [and it] would be quiet for a month…and all of a sudden you have like four in one day,” he says. These numbers, compared to student observations of 1-7 vapers in almost every bathroom at any given point during the day, suggest that dozens of students vape without ever getting help, even if they are addicted.

One reason the number of students who get “busted” is so low is that vape-detecting technology “really isn’t there yet,” which Del Guercio says the school realized after piloting two separate vape-detecting systems. The vape detector would go off about 10 minutes after the vaping students had left. Multiple other students could have gone in and out in that time, leaving the only option to interrogate all students within those 10 minutes.

The systems also resulted in “many false positives,” including the detector going off for non-vape particles from other aerosols like hairspray or perfume. The administration also found that students learned to exhale their vapes toward the floor so the detector wouldn’t respond until minutes later after they’d gone and when the particles had finally risen toward the detector.

Considering this gap between students who are vaping and students who are getting caught or seeking help, the school administration has begun putting more energy into preventing students from starting to vape in the first place, in addition to catching current users.

The school has begun to work in conjunction with The Truth Initiative to display facts, statistics, resources, and helplines on posters that will be hung in student bathrooms. “You’ll see those posters hopefully by the end of the week [Friday 2/23] in every single bathroom,” as of now, these posters have yet to be hung. “Essentially, students that are addicted can text this number. It’s totally anonymous,” says Del Guercio, who thinks it will be beneficial for students to be able to “see that they have a problem” while they are in the act of vaping.

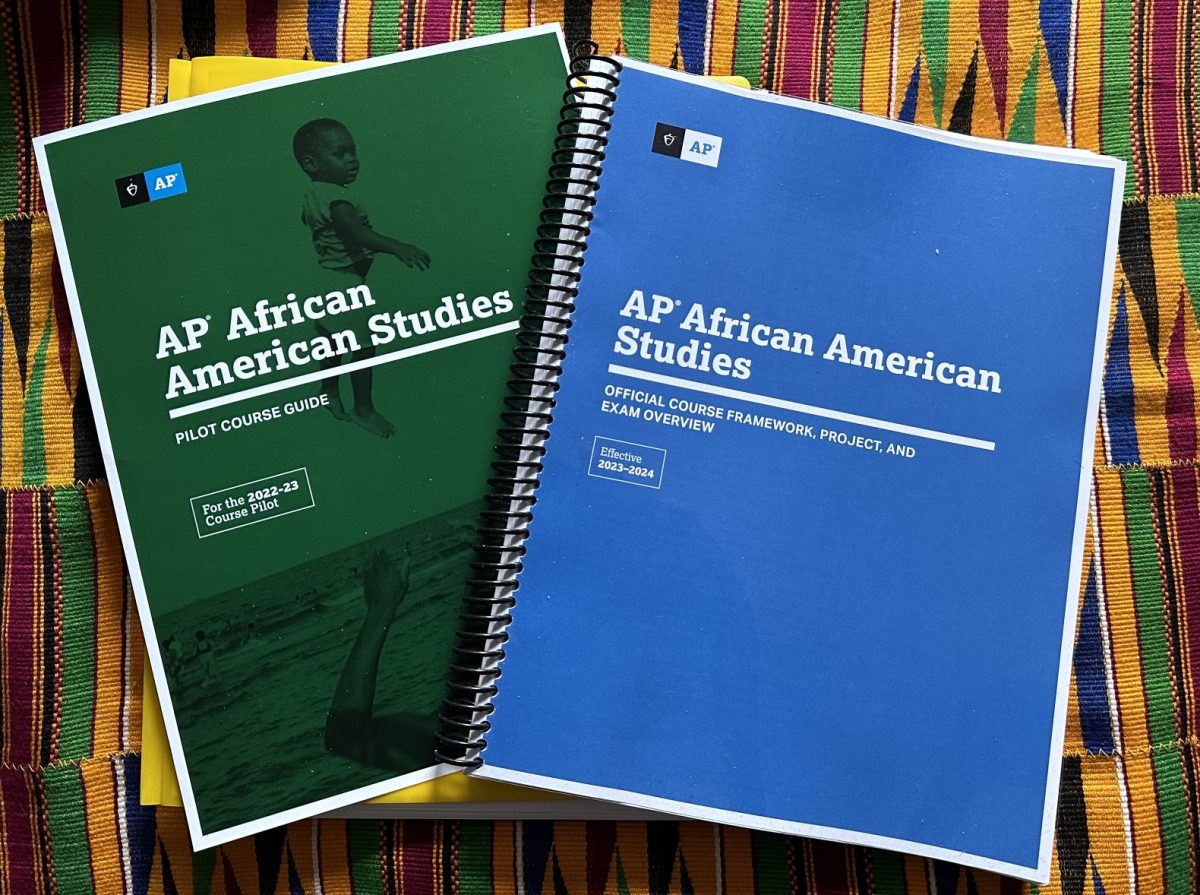

The bottom line for Del Guercio is that education is key. “I already had a discussion with the phys-ed supervisor,” he says, where he discussed the possibility of more thoroughly implementing vaping into all grade-level health curriculums. As of now, the health curriculum at the high school focuses on drugs and alcohol in Junior year. During the first unit of the 11th-grade health class: “Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drugs,” vaping is covered extensively and in-depth. The dangers of vaping, however, are not always acknowledged by students or are being ignored completely, an issue that is bigger than just West Orange.

Starting younger may be a solution, and teachers like Kim Carissimo, a physical education instructor at Liberty Middle School in West Orange have already integrated the topic of vaping into their curriculums. Carissimo has begun to teach 8th graders about vaping and how to identify it as a threat, hoping to reach students before they may become exposed. Where vaping education may be lacking reinforcement, however, is in the 9th and 10th grades, years in which students are often especially susceptible to peer pressure and experimentation. “[It (vaping education)] should be done freshman year because by junior year… you already have a problem,” says Del Guercio, “I think it’s more prevention…than it [is], you know, dealing with addiction. So I think [in] high school [it] should be right off the bat freshmen [year].”

In New Jersey, no “person, either directly or indirectly by an agent or employee, or by a vending machine owned by the person or located in the person’s establishment, shall sell, offer for sale, to a person under 21 years of age” any type of tobacco, cigarettes, or smoking device. The FDA Classifies vapes under the same category as tobacco products, but some states have yet to place them in the same category. Despite the illicit nature of vape distribution, according to a study by the FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration) and the CDC, 2.55 million U.S. middle and high school students reported vaping in the past 30 days (at the time a study was conducted in 2022). Of these numbers, 30.1% of high school students reported vaping daily, and 11.7% of middle school students shared the same.

The CDC reported that while 99% of vapes contain nicotine, “some vape product labels do not disclose that they contain nicotine, and some vape liquids marketed as containing 0% nicotine have been found to contain nicotine,” making it hard for teens to steer themselves away from addiction. It doesn’t help that JUUL pods have 20 times as much nicotine as 1 combustible cigarette, and for teens, the effects of this nicotine are devastating. Up until age 25, your brain develops in crucial ways, using nicotine products harms brain development and targets its attention, learning, mood, and impulse control centers, making the teen brain, already flooded with hormones, unpredictable. Nicotine usage in young brains also causes neuron synapses to be built at a faster rate and makes it easier for kids and teens to become addicted to other types of drugs in the future.

“The most common reason youth give for continuing to use e-cigarettes is ‘I am feeling anxious, stressed, or depressed,’ reports the CDC, and although there are limited mental health studies on the effects of vaping, numerous studies have shown that after quitting, smokers of traditional tobacco products experienced lower levels of depression, stress, anxiety levels. Teens turn to drug usage to cure their mental health problems, but what they don’t know is that vaping could make things worse. Not to mention, the withdrawal symptoms linked to continued often include anxiety and depression themselves.

“The number of times I’ve been in the bathroom and like girls have just been like ‘hey, do you have nic [nicotine]?’” says one WOHS student, “do you understand how easily accessible nicotine is in our bathrooms? That’s insane to me.”

“This morning, there was this girl, and she dropped a vape in the toilet, and they were literally thinking about getting it out. And that’s so disgusting. Imagine being that addicted to vaping,” another student exclaimed.

Starting vaping education early may help to prevent teens from becoming hooked on vaping in the first place, but it’s not that simple. WOHS schools across the nation face a sad reality of youth-oriented marketing tactics, “we are up against multimillion-dollar marketing campaigns that are directed at teenagers through the strategic naming of these products, the design (easily concealable) of the product, and the flavors they use,” explains Del Guercio.

“No measures taken by the school will ever be able to stop the vaping epidemic,” a WOHS student says with unwavering certainty. “Kids are addicted, and it’s a very big situation.”

Still, Del Guercio has hope for the future. But admits that in order “to contend with these companies, our state and federal representatives need to implement more stringent laws and regulations to protect kids.”

Even then, the underlying issues of teen anxiety and depression make this more than just a vaping epidemic. Can Gen-Z still be the generation to end teen addiction?

Correction 3/6/24: An earlier version of this article incorrectly indicated that vaping is not taught extensively in the 11th-grade health grade curriculum, and failed to recognize the efforts by teachers at WOHS and at the middle school level to combat and deter vaping and educate students on its dangers.