Disney released Moana back in 2016, and it was a smash hit. The movie earned almost $650,000,000 worldwide ( about $500,000,000 more than the movie’s budget of $150,000,000), was Certified Fresh by Rotten Tomatoes with a 95% critic score, and even earned Disney yet another Oscar nomination for Best Animated Feature in 2017. Nonetheless, the movie’s success is not over, as Moana fever still rages throughout the world. The popularity of Moana even peaked as it became the most streamed movie of 2023, with over 11.6 billion minutes watched.

With the success of Moana, it makes sense that Disney would attempt to make some extra money off of the film. Whether it’s a new addition to their theme park, a sequel, or even a live-action adaptation, Disney is making an attempt to expand Moana’s financial income even more than it already is. Yet, Moana isn’t all sunshine and rainbows for Disney and their plan to “create authentic and unforgettable stories, characters, experiences, and products,” as the movie has numerous flaws in terms of the representation of Polynesian culture and mythology.

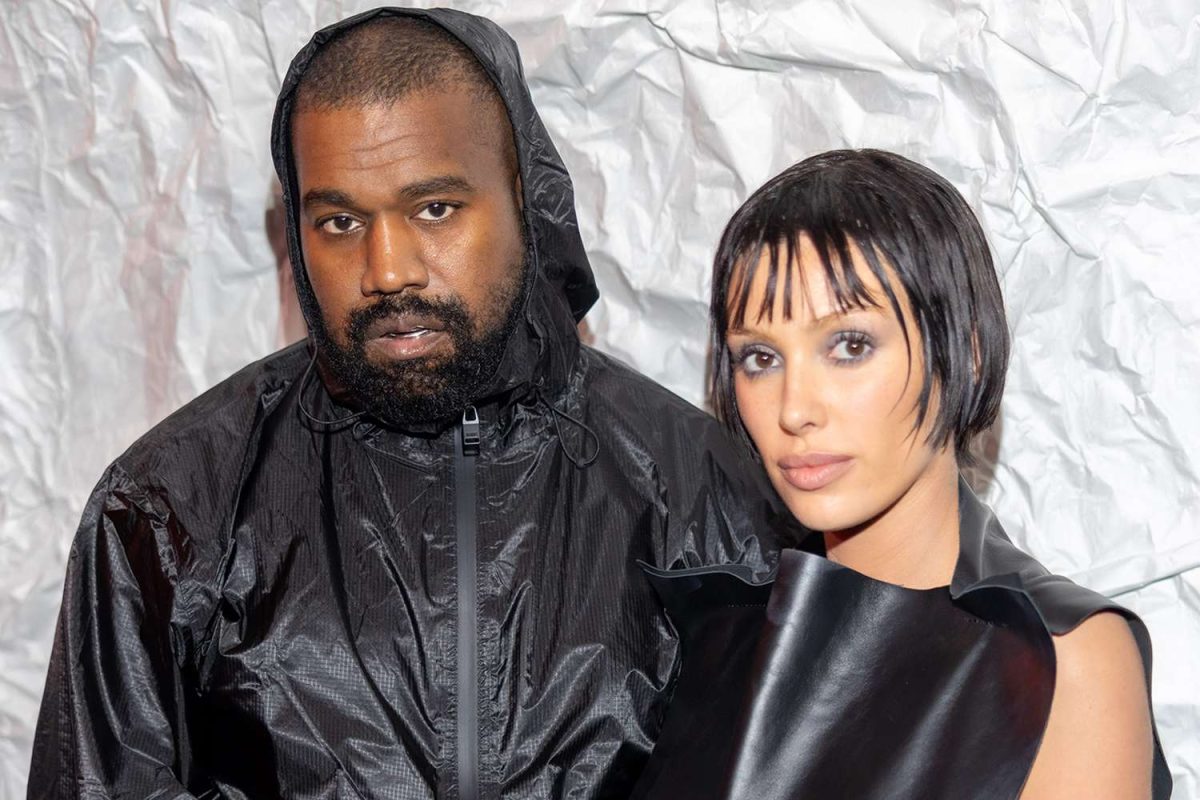

One of the main criticisms came from the movie’s representation of the Polynesian demigod, Māui (or Maui), who is voiced by Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. Firstly, Maui’s physical appearance has been heavily critiqued. “For one thing, he’s big, really big. He also has a great head of thick, wild hair (in most versions, Maui’s hair is tied back in a neat topknot) and biceps bigger around than his co-star’s waist,” wrote New York Times reporter Robert Ito in his article on the adaption of the character. Later in the same article, Preston McNeil, who directed the short film, “Maui and the Sun” said that seeing Disney’s Maui “was definitely a shock” he would go on to say that Maui is “the youngest [of his brothers], and cheeky, so you don’t think of him as a big man.”

While on the surface, the change in Maui’s weight did not seem offensive, when Moana was released, it was immediately deemed offensive. Many critics of the portrayal of Maui pointed out the stereotype that Polynesians, and Pacific Islanders in general, are overweight and lazy. So, Maui being portrayed as a larger man was seen as Disney feeding into that stereotype. It was a point that Ito brought up in his article and was even said by Smithsonian Magazine writer Doug Herman’s Native Hawaiian friend (Trisha Kehaulani Watson-Sproat), who stated in Herman’s article, “Our men are better, more beautiful, stronger[,] and more confident…As much as I felt great pride in the Moana character…Maui[‘s] character left me feeling very hurt and sad. This is not a movie I would want [my son] to see. This Maui character is not one I… think is culturally appropriate or a character [my son] should want to be like”.

Another problem with Maui was that his story was just plain wrong. “As a Tongan cultural anthropologist who has been critical of Disney’s Moana…I went to the theater, bracing myself for the Disneyfication of my culture. Minutes in, it became obvious that despite its important girl-power message, the film had a major flaw. It lacked symmetry by its omission of a heroic goddess [Hina],” wrote Tēvita O. Kaʻili in his article, “Goddess Hina: The Missing Heroine from Disneyʼs Moana.” He later goes into detail about the issues of removing Hina as it “is a form of colonial erasure that amounts to failure in oceanic proportion,” and that “it is a clear symptom of a much deeper problem…Disneyfication of Polynesian tales produces shallow versions of deeply complex indigenous stories…[this is the case with] extracting the god Māui and discarding his complementary deity, the goddess Hina.”

But Maui isn’t the only complaint that fans have about Moana. One of the other main problem areas that Polynesian people pointed out was Disney’s portrayal of the Kakamora who, according to Kauai Calls’ article, Disney’s “Moana,” Compared to True Hawaiian Culture, “is a short[-]statured mythical group of people from the Solomon Islands, similar to the Menehune dwarfs of Hawaii” Kauai Calls even goes on to say that, similar to Maui, “The depiction of the legendary Kakamora people in the movie is also incorrect…In real Polynesian lore, they do not act or look like the movie depiction.”

Another issue regarding the Kakamora and the movie in general is the use of coconuts. The Kakamora wear coconuts as armor, which is in no way similar to Polynesian lore, and the Moana characters sing, “Consider the coconut…We use each part of the coconut. That’s all we need. We make our nets from the fibers. The water is sweet inside. We use the leaves to build fires. We cook up the meat inside. Consider the coconuts. The trunks and the leaves, ha,” in one of the first songs of the movie “Where You Are.”

The use of coconuts throughout the movie is defined by Herman as the “happy natives with coconuts trope” and “tiresome and cliché.” Herman continues to say that coconuts “are part of the shtick of caricatures about Pacific peoples.” The coconut armor of the Kakamora is also an issue because, as Herman writes, “‘Coconut’ is also used as a racial slur against Pacific Islanders as well as other brown-skinned peoples. So depicting [Kakamora] as ‘coconut people’ is not only cultural appropriation for the sake of mainstream humor but just plain bad taste.”

The list of problems that Disney’s Moana presents in terms of AAPI representation is extensive. With Moana 2 and the live-action movie coming out, the question remains if Disney will improve upon its AAPI representation to better reflect its statements on diversity and inclusion within its films.