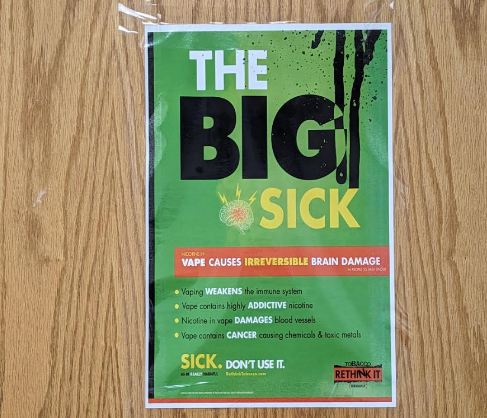

During the last week of April, the administration hung up vaping awareness posters in bathrooms across the school. The posters were meant to be put up by March 23rd, but due to delays in the printing process, Principal Guerrero said this distribution was delayed. These posters are brightly colored with phrases like “If you don’t think vaping is addictive, it may have already altered your brain” and “Vaping. Don’t get taken in.” Some of the posters outline the harmful effects of vaping and its toll on the body, including a weakened immune system and blood vessel damage. Others display the toxic metals and chemicals in vapes, like lead, cadmium, and acetone, that can cause irreversible damage and cancer. The posters also offered QR codes and addiction helplines.

These posters were proposed as one of the plans of attacks mentioned by Mr. Del Guercio, a dean at WOHS, who spoke to The Pioneer in March. As of now, the administration has yet to introduce any other forms of vaping prevention or intervention. Guerrero admits that he does not “think [he is] qualified to call it [the vaping situation at WOHS] an epidemic,” and instead is regarding the problem as “a significant concern…[that is] significant enough where it does have our full attention.” Guerrero explains that the issue, although significant, is not unique to WOHS and is instead a pervasive issue in high schools across the state and the nation. “I belong to a cohort of Essex County principals that meet every couple of months,” says the Principal, “[vaping is] always something that comes up, and we’re all looking for answers on how to best…address [it].”

Guerrero attends every WOHS PTA meeting and says that vaping has been a hot topic in recent months. The organization has talked about “working in collaboration with our parents” to bridge the gap between parents and their children and help parents recognize vaping devices within their home. At this point Guerrero says, between his discussions with parents and teachers from both West Orange and other districts, “everyone’s… for the most part, in the same situation,” and that as of now there have not been any groundbreaking tactics or resources used by other schools in response to vaping even though districts are “constantly exchanging ideas and, you know, sharing speakers and presenters.”

Even though the administration hasn’t proposed any major changes in policy to combat vaping in school, the problem hasn’t flown under the radar of other WOHS staff. Mr. Alvine, the health department supervisor at the highschool along with 9th grade physical education and health teacher Mr. Patscher sat down to discuss the battle against vaping they’ve taken up within their own classrooms and the importance education plays in stopping it.

“We are supportive of the administration,” says Alvine, though Patscher acknowledges that it would be nice if the health department, as “proponents of health and physical education,” work to “spearhead” anti-vaping education. He proposes setting up a table with resources to provide to students and the possibility of setting up “field trips to certain facilities,” in order to form more positive connections with students. Even though punitive measures are important, especially since vaping is illegal for minors, Alvine offers that it may be helpful for students to see that vaping isn’t just an action met with punishment; it’s an action met with severe health consequences. “We’re not the administration we’re not, you know, catching kids in the bathroom, we’re trying to…prevent it.”

“Vaping is becoming a national epidemic,” Alvine says, “it just breaks my heart to see kids addicted.”

Patscher and Alvine talk about vaping from a unique perspective, like they mentioned, their job is to address vaping from an education standpoint rather than a disciplinary one. As health educators, they are tasked with covering a lot of subjects in their curriculums and in a relatively short period of time. For each grade, their health unit typically lasts for about 10 weeks out of the 36-week school year.

At the highschool, ninth graders are taught three different units, one of them is “wellness” which includes aspects of physical, emotional, and social wellbeing. This past winter, “we started to include teaching anti vaping under our physical health [unit],” says Patscher. This is followed by driver’s education in tenth grade rather than a health class. Vaping education is brought back up the next year when Juniors have a drugs, alcohol, and tobacco unit which delves deeper into the dangers of drug use. Of course, this is in addition to the “disease, health conditions, relationships, pregnancy and parenting” lessons taught in the same year.

“We’re mandated, also, to teach CPR before kids graduate,” says Alvine. So in senior year, twelfth graders go through a CPR course. Alvine describes the health curriculum at the high school as “jam-packed” since teachers are required to fit a plethora of topics with “a million standards” into 10 short weeks.

For Alvine, these 10 weeks just weren’t enough. “Health really should be a full year course,” because, he explains, “without your health you have nothing.” 4-5 years ago Alvine started the Elementary Health Program in the district, working closely with teachers to introduce kids in grades one through five to key aspects of wellness. “Starting in grades three, [we] start to talk about E-cigarettes and the dangers of vaping,” says the supervisor, who stresses the importance of establishing “building blocks” early on for students.

Alvine describes the district program as a “waterfall” that hinges on repetition. “We’re going to be redundant,” says Alvine, who says the goal is really to “keep hitting the dangers of this [in] hope that it sinks in.” Patscher compares the tactic of repetition in education to brushing your teeth. He explains that small habits like the act of brushing your teeth twice a day have been ingrained into your routine since you could walk due to repetition. Simmiliary, addictive patterns like vaping can be the same way, but so can the conscious decision to say “no” and focus on healthy habits.

This winter health educators from both middle schools and WOHS met to analyze the “vertical articulation” of the program, and brainstorm new ideas to fill the gaps where vaping education may have been missing.

Even with the “building blocks” in place there’s so much more to vaping education than what’s on the surface. Patscher explains how teachers not only have to teach about the health risks of vaping, they also have to educate students on how to protect themselves against marketing that targets young people. While many e-cigarette companies rely on targeted advertising to sell their products, Patscher demonstrates how persuasion can work both ways.

Patshcer has begun using interactive activities to solidify his message and persuade students to say no to vaping. In one lesson he instructed his ninth graders to complete a circuit of exercises two times. The first time “regularly” with no modifications. The second time, students would complete the circuit while breathing through a paper straw to simulate what vaping can do to your lungs and airways during physical exertion. “Half the kids after twenty seconds were gasping for air,” he says, and many expressed how they never wanted to feel like that again. Patscher used this as an opportunity to explain to kids that vaping“is going to destroy the alveoli in your lungs” and it’s not just “water vapor.”

“I’ve noticed…[that by] engaging them in activities [they] are going to ask more questions after,” Patscher says he also employs the use of “scare tactics,” which Alvine stands by as well. A slide presentation for the eleventh graders’ drugs and alcohol unit showed graphic images and videos of what could happen after extended exposure to vaping, and detailed health side effects including “popcorn lung” and gum disease.

“My wife and I, we really tried to scare our kids,” Alvine says, explaining that within his own family he outlined the severity of the issue in “hope[s] [they didn’t] make these choices.”

Alvine doubles down on the importance of setting good examples for kids as both teachers and parents. “To be a good role model for your kid goes a long way,” he says. While he notes that “there’s always an exception,” and even students with the most supportive guardians could still face the possibility of falling down the slippery slope of drugs and addiction, he’s observed that “there’s more success” when parents set the right example for their child.

Patscher describes what he calls, “a bell-shaped curve,” referring to what is known as Normal Distribution in statistics. On one side of the curve, he places 10-15% of students who are exceeding academic standards and doing very well developmentally. Patscher then moves on to the 50% in the middle who are meeting expectations. On the opposite end of the spectrum he recognizes students who may lack a support system they need at home. “Those are the kids it’s hard to reach,” he says, using this as an opportunity to reflect on the decisive impact “inclusive” health and vaping education can have on students.

“I think we have a lot of caring people [at WOHS],” Alvine adds, stating, “we need parents and we need community…we can’t cure all the ills in health class.” Patscher tries to keep parents informed by sending email correspondence with vaping prevention and help resources home, awarding students an extra credit point if their parent responds to the email with a “thumbs up”. “Otherwise,” he says, “it’s tough to bridge that gap between school and home.”

While adults need to be pillars in the vaping prevention cause, students also play a role too. In March, students shared their experiences with staff members’ responses to students vaping. Some shared stories about teachers or security guards letting vapers go unreported. Principal Guerrero says that “in the spirit of making the school a better place,” the best thing for a student to do would be “report that type of behavior” if they experienced a staff member underperforming in regards to students safety. At the beginning of the year staff members are required to complete an online training course that outlines symptoms of substance use among students and their responsibilities in regards to student safety. The training is mandated as part of

N.J.A.C. 6A:16-3.1 which states that “all staff members receive in-service training in alcohol, tobacco, and other drug abuse prevention and intervention.” The training alerts staff members that they are “responsible for following district protocols for prevention, intervention, referral for evaluation and treatment, and continuity of student care.”

“We could definitely use more in regards to helping train our, our, our teachers,” Guerrero says, noting that supplementary training in addition to the meetings and online training at the beginning of the year would be beneficial as the quantity of staff education about vaping specifically is “not as much as [he’d] like.”

Students stand at the forefront of the fight against vaping because they are far more connected to their peers than adults. The biggest hurdle Patscher says that health teachers face while trying to teach about the dangers of vaping in school is the “cool factor”.” He says that kids are attracted to certain things, even from a young age, toys like “little toy skateboards” stand out to kids if they see their peers playing with them. “Trying to get past the ” that tobacco and e-cigarette corporations have embedded in their marketing schemes could be helped by “highlight[ing]… some of our students that are leading a healthier lifestyle,” says Patscher. He says that by saying “no” to peer pressure and vaping, students can help break down the facade of appeal.

“People have always looked up to sports and athletes,” Patscher adds, explaining that student-athletes need to take initiative and establish boundaries when it comes to pressure from friends, “you need to be strong because your friends are going to give you a lot for it.”

Besides continuing to reveal the science behind the health risks that come with vaping in their health class, Patscher and Alvine outlined some new ideas, including the formation of a “school-wide campaign that has resources faculty, staff, parents and students,” says Patscher. “I’ve been researching campaigns with the FDA called ‘The Real Cost’,” a campaign that provides schools with resources and free posters. Patscher notes that a campaign like this would “[get] the entire staff on board to say maybe the punitive things are not the best…if you’re addicted, you’re going to find a way to grasp your addiction and bring it wherever you want.”

Patscher told The Pioneer that he aims to set up a meeting to discuss these proposals with Principal Guerrero.