Problems with POC

The more we learn and grow, new words are added to our vocabularies to enhance our understanding of various topics. Among these new words, the term “POC” or Person of Color has taken the forefront for inclusion as a catch-all term to refer to individuals who are not white.

Originating from the 14th century, the word colored was first used in relation to any race or ethnicity other than white. During the Jim Crow era of the United States, colored was used as the legal racial descriptor for African-Americans and was coined by civil rights activists like Martin Luther King in the 60s, until it gained full popularity in the 1970s. In some places like South America it has taken a special meaning that specifically refers to multi-racial communities. Eventually, language surrounding non-white people went on a journey from colored, to minorities, to people of color, which is commonly used today.

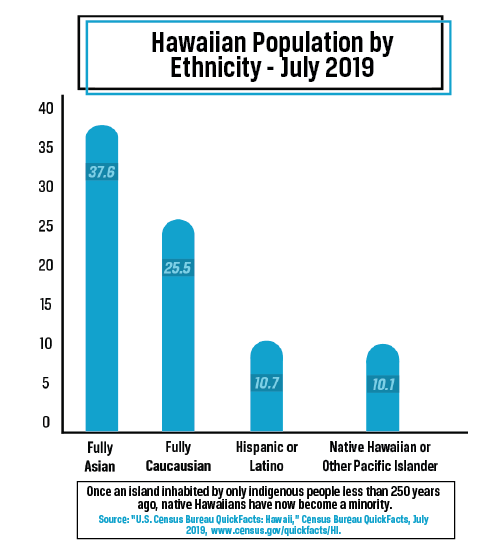

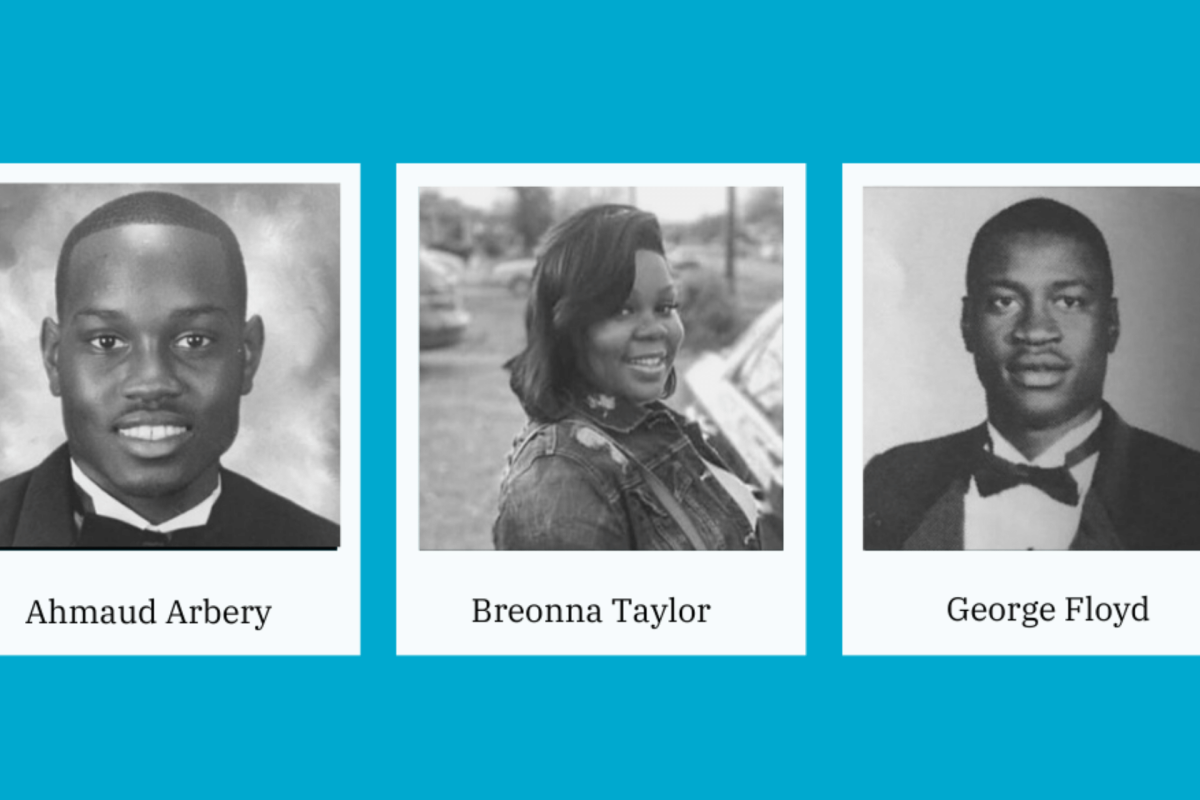

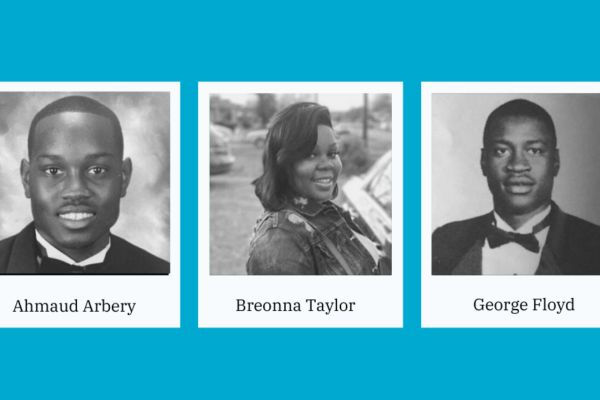

Firstly, as a young black woman I acknowledge the efforts made by my generation and those before that transformed racial terminology to be inclusive and comprehensive, but ironic enough that poses some problems. No word or phrase is inherently bad, but when accounting for the many different intersections and experiences of marginalized people, it is important to be as nuanced as possible. “POC” creates the impression that all non-white people share the same struggles or perspectives. While symptoms of racism and discrimination are alike, the way this manifests across identities is very different. For example, African-Americans were enslaved and dehumanized for 400 years and arguably longer; after-effects of this enslavement still trickle down today and impact the Black community in unique ways exclusive to the Black-American experience. That did not happen to POC, but Black Americans specifically. To claim that distinct aspects of racism affect POC as a whole masks differences in power and privilege between different ethnic groups. These differences even exist within shared ethnic groups like southeast Asains vs. pacific islanders who face unique challenges and discrimination. This homogenizes all non-white people, stripping us of our cultural and ethnic identities that directly impact who we are and how we are treated.

The designation can also come off as rather divisive with whiteness at its center. It assumes that whiteness is the norm or default state and non-white people are the exception. This type of “othering” enforces that white culture is the central and superior culture, and other races and ethnicities are a deviation from white normality. I am not suggesting that POC is removed from our vocabulary as a whole, but rather emphasizing the need for intersectionality in important conversations about race. It is crucial to be aware of the linguistic limitations for certain words and strive to use precise language that is inclusive of diverse experiences and identities.