WOHS Senior’s Play on Gun Violence Wins Playwriting Contest

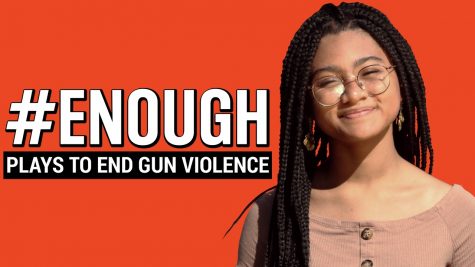

West Orange High School senior Olivia Ridley was among the seven winning playwrights selected for their submissions to #ENOUGH: Plays to End Gun Violence, an organization dedicated to “promot[ing] playwriting as a tool for self-expression and social change.”

Her play, Ghost Gun, is the protagonist Black Boy’s “villain’s monologue” to the audience. With Black Boy’s self-perceived decay, he holds the audience at gunpoint in an explosion of outrage and distress, creating a perceptive and meta story which addresses our time of alienation, poverty, racism, mass media, systemic violence, and gun violence.

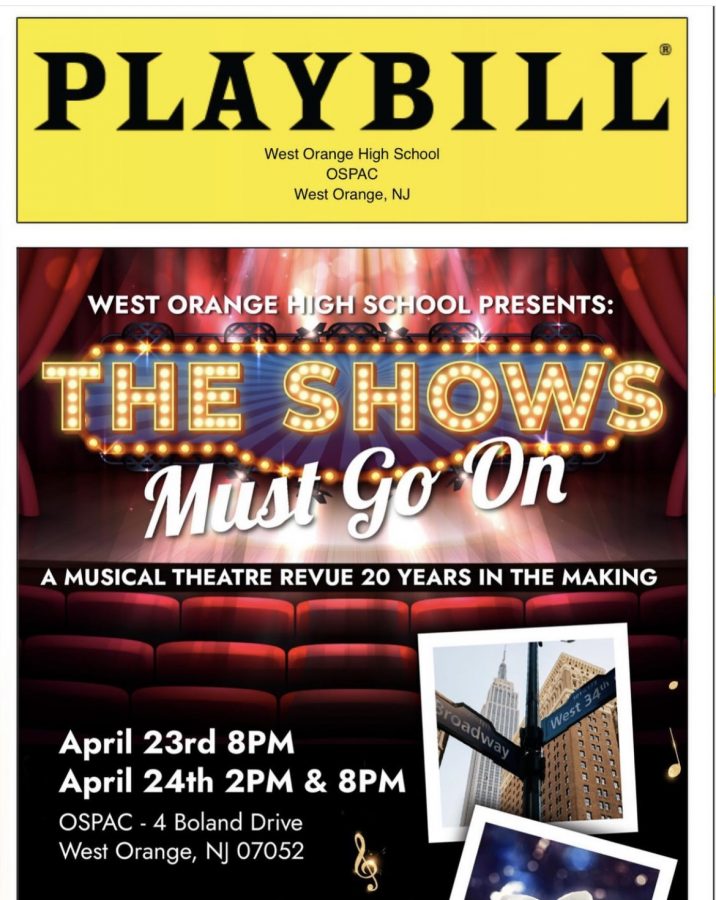

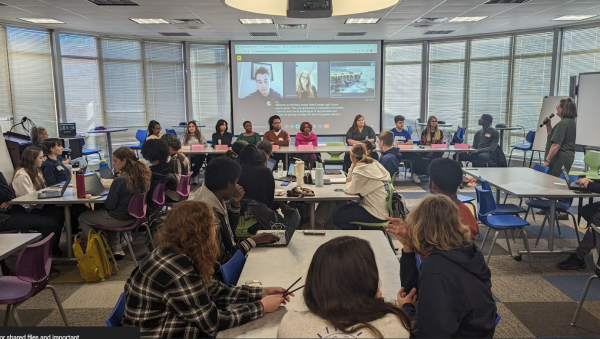

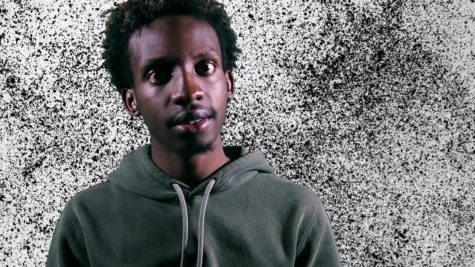

On Dec. 14, the eighth anniversary of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, the WOHS Thespian Society released a staged reading of every play, with Ridley herself playing Black Boy in Ghost Gun. Details on other performances can be found at NJ.com’s article.

The following is an interview with Ridley.

Please give a brief description of what Ghost Gun is about.

So Ghost Gun is from the perspective of a young black boy and he’s propelled by this idea that he is decaying and that he’s rotting. He’s just searching for a way to be heard. The monologue takes place as the “villain’s monologue” — the speech given to the hero right before the hero is killed in a movie — to his audience held at gunpoint.

How did you decide on the core concept of your play?

When approaching the contest in general I was trying to determine what I felt needed to be discussed more in the gun violence conversation. School shootings take the center stage of the conversation, which is incredibly important, but gun violence is a very far reaching and complex issue with a whole bunch of different components and facets. I tried to find the ones I felt like weren’t spoken about enough, which were race and class. I tried to incorporate that in the piece to introduce these concepts to the conversation. These are narratives that I felt really needed to be represented.

You focus on decay, rotting, and ugliness in your play. What brought you to emphasizing that?

The general fear and insecurity of young black men in America. It’s interesting, because words like insecurity and fear aren’t really associated with young black men, but I think they absolutely should be. You have a culture and society that constantly tries to reassert to these young men that they are unworthy, inherently aggressive, violent, and something ugly. How do you fend that off, especially as a young black boy? I wanted to bring forth that idea of having sensitive young black men and the insecurity that a lot of them had developed as a result of what is generally thought of black men in our current media and culture.

You’ve mentioned that you enjoyed the collaboration aspect of #ENOUGH. What was that like and who did you work with?

In the beginning of the process we had three workshops where the seven — six other [playwrights] were selected. At these workshops all of us would meet and read each other’s plays and workshop them by doing writing exercises and critiques. We got to work with Crystal Skillman and Fred Van Lente — two other playwrights and artists — who gave us critiques. I ended up learning an incredible amount of information from just collaborating with those other playwrights and artists.

What were your friends and family’s reaction to winning the contest?

It’s really funny ‘cause I kept it on the down low. I didn’t run and tell my family, I kept the whole competition on the down low, and I was just like, “hey there’s a scholarship opportunity and so this is what I think I’d like to do.” So when I got the feedback, no one was really expecting it; I submitted my play the day that it was due, so it was shocking. We were very excited but also shocked.

How about the media attention you’ve gotten?

Yeah. [Laughs.] Strange and shouldn’t have happened! Yeah! That’s also been very strange and very unexpected. Again, I entered this whole situation thinking this was a scholarship opportunity, not really recognizing all that I would reap from this opportunity which I am just so tremendously grateful for. Last Friday I had the opportunity to speak on a panel with two of my playwriting heroes — David Henry Hwang and Dael Orlandersmith — having a discussion with them about arts and activism. That is an opportunity I don’t think I would have ever been granted or given otherwise. So I am just really grateful for all the attention that this entire project has gotten.

We were really excited that productions have been performed across four different continents. I truly hope that people are beginning to acknowledge and discuss this issue. We treat school shootings as a moment and not as an expansive and long-term conversation, so I hope that this project has had the opportunity to rekindle some of that dialogue.

This isn’t your first time writing about gun violence. In 2018 you wrote and performed the poem “Lockdown Procedure” during the WOHS student walkout for gun control on April 20. Did you look back on that piece when writing Ghost Gun?

Absolutely. Even though my play doesn’t have to directly do with school shootings, I think a lot of the energies surrounding that poem and that piece are also present in Ghost Gun. Even though they are about very different issues, they’re still a part of the same conversation. So I did definitely return to that a little bit.

I think at the time I wrote the poem I wasn’t aware that gun violence, well, you know, there are other parts to this conversation other than school shootings. I thought that school shootings were kinda the center and the propellant of this conversation. I think in retrospect I can definitely say now that I have a more — I keep using the word extensive — but like, extensive understanding of everything that this issue encompasses now. Which is why I wrote a piece that didn’t have to do with school shootings.

Aside from #ENOUGH, you also won another playwriting contest held by West Orange’s Luna Stage for your play Slush. Can you describe that play?

Sure! It’s basically a short play. It’s a conversation between two people. It takes place at a 7-Eleven, I think at like three in the morning. It’s a play depicting a conversation about medically assisted suicide. They stand at two opposite ends of the issue, showing how communication — over that very complex issue — would go.

You made a comment about how you wrote Slush’s protagonist with the intent of giving “a voice to normal people.” What drew you to this angle again with Black Boy?

I think that art is the perfect medium to provide those voices and it just made sense to me to hold that responsibility of bringing forth these perspectives and trying to spark these conversations that I don’t feel like we’re having yet. It doesn’t make sense for art to be repetitive because you lose such a valuable opportunity. You have this opportunity to speak directly to your audience and I feel like we should take advantage of that. While we have everyone gathered in a room, give a voice to those who may not typically have one.

Can we expect that from your future projects?

I can quite confidently say so, I think. Yeah.

In your interview with #ENOUGH, you said that your influences include Toni Morisson, Daveed Diggs, and “various French philosophers.” Care to list some of those philosophers?

Albert Camus definitely, Jean-Paul Sartre, and — why am I blanking on his name? He wrote like Black Skin, White Masks—

Frantz Fanon.

Yeah, thank you.

Any works by them you particularly like?

Black Skin, White Masks is incredible. Nausea and The Plague. Nausea is by Jean-Paul Sartre and The Plague by Albert Camus.

[We go on a tangent about philosophy and Marxism for a few minutes, discussing Guy Debord, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and reading recommendations.]

Has any piece of media grabbed your attention recently?

Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal, who are two of my favorite artists in the whole wide world. In 2018 they came out with the movie Blindspotting, which just has to be one of my favorite films of all time. It’s just geniously written, directed, and the actors are brilliant, and everything about the script is so brilliant. And that’s becoming a TV series which I am definitely ecstatic about. Daveed Diggs also has a song that did come out [in] like 2015 and it’s upsetting that the message is still so relevant, called “Knees on the Ground,” and that is definitely a piece that drives me forward as well.

Do you have any words of wisdom or final statements for our readers?

Don’t look away. That’s kind of the slogan of #ENOUGH, but like confront issues head on, and have difficult discussions, and create the dense and complex and nuanced art. I think some of the best and most important conversations are the hardest to have.